Norway’s villages

Norway’s dramatic scenery is famous the world over, but tucked between the fjords and mountains are small villages that tell the country’s deeper story—of Vikings and miners, cod fishermen and copper barons, timber merchants and daring railway engineers. In these tiny communities, history isn’t locked in a museum; it is painted onto sea-bleached boat sheds, whispered from wooden bell-towers and baked into the salty timbers of century-old rorbu cabins. What follows is a village-by-village ramble of roughly 3 100 words that shines a light on ten of Norway’s most evocative hamlets, tracing how each grew, faltered, modernized and—in many cases—reinvented itself for a new era of mindful travel.

Roros – From Copper Frontier to UNESCO Landmark

High on the mountain plateau where winters bite at –40 °C sits Roros, a settlement founded in 1646 after rich copper veins were discovered. The Danish-Norwegian crown granted the fledgling mine an enormous “Circumference”—a 45-km-radius resource zone whose forests supplied charcoal and whose farmers hauled ore by reindeer sledge. Burned to the ground by Swedish troops in 1679, the town was rebuilt in signature tar-black timber and continued smelting for three centuries. When the works finally closed in 1977, preservationists moved quickly; today over 2 000 wooden buildings, slag heaps and an ice-age transport route make up a UNESCO World Heritage site and a living open-air museum where reindeer herders, artisans and eco-chefs share the narrow lanes with visitors.

Reine – The Crown Jewel of Lofoten

Reine looks almost imaginary: red cabins on stilts, emerald water rippling beneath 800-metre granite horns. Yet this tiny outpost has been a trading hub since 1743, its sheltered harbour vital to the seasonal skrei (migratory Arctic cod) boom that fed Europe. Nazi reprisals in 1941 saw parts of the village torched, but Reine bounced back, and a 1970s magazine poll even crowned it “Norway’s most beautiful village.” While fishing continues, tourism now dominates; hikers climb Reinebringen for the iconic panorama, kayakers weave among the islets at midnight-sun o’clock, and winter guests chase aurora across a sky so clear locals call it “the glass dome.” Carefully managed visitor caps and community-run lodges ensure the harbour remains a working one, not a postcard stage set.

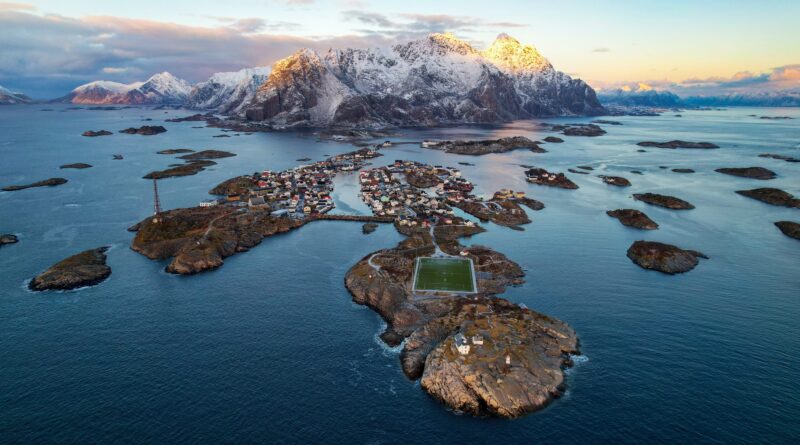

Henningsvær – Venice of the North

Spread across two skerry islands and stitched together by elegant 1980s bridges, Henningsvær grew from four residents in 1769 to a cod-season metropolis of 1 000 souls by 1950. Village owners such as Jorgen Zahl and later Jens P. B. Dreyer built salting stations, canneries and the iconic rows of rorbuer that still fringe the harbour. A massive breakwater (1934) made the anchorage safe enough to lure entire fishing fleets, while modern road links opened the doors to art galleries, climbing festivals and the world-famous football pitch perched atop drying racks. Locals like to say the salt in the air is half sea, half history—and when gulls wheel over the cod racks at dusk, it’s easy to believe them.

Nusfjord – Time Capsule of the Cod Trade

If you could sail back to 1890 you might find Nusfjord unchanged. Tucked inside a notch of fjord on Flakstadoya, the village was one of three Norwegian pilots chosen for UNESCO architecture preservation in 1975. Nineteenth-century storehouses, a wharfside sawmill and ochre-painted rorbuer survive intact, now forming the heart of Nusfjord Arctic Resort. Archaeology hints at settlements as early as 425 BC, and by the “golden age” more than 1 000 seasonal fishers thronged the harbour. Today just nineteen year-round residents keep the lights on, welcoming travellers to bake flatbrod in the old bakery, row wooden faerings between cormorant-speckled skerries and learn how stockfish once bankrolled a nation.

Flam – Rails, Rallars and Reinvention

Flamsdalen’s steep walls nurtured Iron-Age farms, but the modern village story pivots on engineering. In 1923 navvies began blasting tunnels for Flamsbana, a 20-km branch of the Oslo–Bergen line that descends 866 m to fjord level through twenty hair-pin tunnels, eighteen hewn by hand. Opened in 1940 and electrified in 1944, the line linked remote farms to city markets and later delivered wave after wave of camera-clicking rail buffs. Earlier, a 19th-century emigration wave saw some 500 Flam residents sail for America; their stone-and-timber strip farms gave way to mechanised agriculture, while the old construction road, Rallarvegen, was reborn in 1974 as Norway’s greatest bicycle trail. Today visitors pedal past waterfalls, duck into the 1670 stave-style Flam Church and toast the view aboard an electric fjord cruise—proof that sustainable tourism can ride the same tracks industry once laid.

Undredal – Of Goats, Legends and a Pocket-Sized Stave Church

With just 100 residents and 500 goats clinging to the cliffs above Aurlandsfjord, Undredal feels lifted from folklore. Legend tells of two sisters who gifted the 12th-century stave church and irrigation ditches to the village; carbon dating of nearby foundations suggests a kernel of truth. The church, consecrated to St Nicholas, is Scandinavia’s smallest—only 40 seats—and once stored goat cheese wheels in its attic. Cheesemaking, in fact, underpins village life: sweet brown geitost caramelised over open fires still ships worldwide. Arrive by boat and the first scent on the wind is wood smoke mixed with whey; stay past dusk and you may hear kulokk, the haunting goat-herder’s call, echoing off the fjord walls.

Lærdalsoyri – Trading Port Turned Phoenix

Strategically placed where the Lærdalselvi river meets mighty Sognefjord, Lærdalsoyri flourished as a packet-boat stop on the Bergen-Oslo mail run. Merchants built 161 wooden houses—Swedish empire façades, salmon-pink inns, salt stores—mostly between 1700 and 1870. Disaster struck in January 2014 when hurricane-force winds whipped a house fire into a conflagration that consumed 30 buildings and forced midnight evacuations. Miraculously, the protected heritage quarter (and twin-towered 1869 Hauge Church) survived. Rebuilding plans now balance sprinkler upgrades with historical authenticity, and summer sees the old Oyragata alive again with marche stalls, jazz gigs and Nordic food pop-ups. As one craftsman told reporters: “Our future is in the past—but with better fire hoses.”

Geiranger – From Isolated Farms to Fjord Superstar

For centuries Geiranger’s handful of farmsteads clung to ledges 400 m above a sapphire fjord, reachable only by rowing or goat track. A mountain road blasted through in 1889 transformed everything: steamships followed, Kaiser Wilhelm II made the valley fashionable, and by 1900 cruise calls had doubled. Hoteliers erected clapboard grand hotels such as Union and Utsikten, while locals ferried visitors to the Seven Sisters waterfall and sold embroidered bunads from porch-side stalls. Today roughly 800 000 arrive each summer, yet strict emissions rules (zero-emission fjord by 2026) aim to keep the UNESCO-listed waters clear. Look past the selfie sticks and you can still trace medieval field strips, 15th-century church timbers and the same snow-robed peaks that enchanted Europe’s crowned heads.

Balestrand – Dragon-Style Villas and an English Love Story

Artists arrived first, drawn by mirror-calm Esefjord light; then came Margaret Green, an English vicar’s daughter who married hotelier Knut Kvikne in 1890. Tuberculosis claimed her four years later, but her dying wish—to build an Anglican church—birthed St Olaf’s, a dragestil (dragon-style) stave-inspired chapel consecrated in 1897 and later immortalised in Disney’s Frozen coronation scene. Alongside the church, Balestrand showcases dragon-head-carved verandas, the art-packed Hoyvik hall, and a waterfront of Swiss-chalet villas once dubbed “Little Switzerland.” In summer, cider orchards scent the air, and mail boats still whistle in from Bergen, keeping alive a tradition that predates roads by half a century.

Skudeneshavn – White Timber and Sails on the South-West Tip

An 1858 ladested (licensed port) at the mouth of Boknafjorden, Skudeneshavn exploded during the age of sail when herring shoals flickered silver just offshore. Shipowners invested their profits in dazzling Empire-style houses whose elaborate fretwork earned the nickname “White Lady Town.” By the late 19th century the harbour boasted 130 sailing vessels, chandlers and even rope-walks; today fewer than 3 500 residents remain, but every July the Skudefestivalen gathers 600 historic boats and 35 000 visitors for four days of shanties, tar-scented engine demos and open-house tours. Stroll Soragada’s narrow lane and you’ll see gardens the size of row-boats—so precious was dockside land that sailors planted roses wherever an anchor once dropped.

The Threads That Bind

Across these ten villages a common pattern emerges: natural resources sparked initial settlement—copper, cod, fertile pasture or a deep-water quay. Isolation preserved wooden architecture long after mainland towns embraced brick, while 19th-century road and rail projects cracked open fjordland geography and ushered in tourism. Twenty-first-century challenges now centre on sustainability: balancing cruise crowds with zero-emission targets, wildfire risk with timber heritage, and heritage authenticity with the Airbnb boom. Yet Norway’s villages are tackling those dilemmas with the same ingenuity that once hauled copper over frozen lakes or bored tunnels through mountains—electric ferries in Geiranger, green cod-drying tech in Henningsvær, heritage-funded fire-sprinklers in Lærdalsoyri, community visitor caps in Reine. Travellers who linger—who buy brown goat-cheese direct from Undredal farmers, cycle the old navvy road in Flam, or carve cod-liver soap beside Nusfjord’s sole carpenter—help keep those solutions viable.

CLICK BELOW TO KNOW MORE